Check out the project at https://github.com/grjte/groundmist-sync

Cross-posted to my atproto PDS and viewable at Groundmist Notebook and WhiteWind.

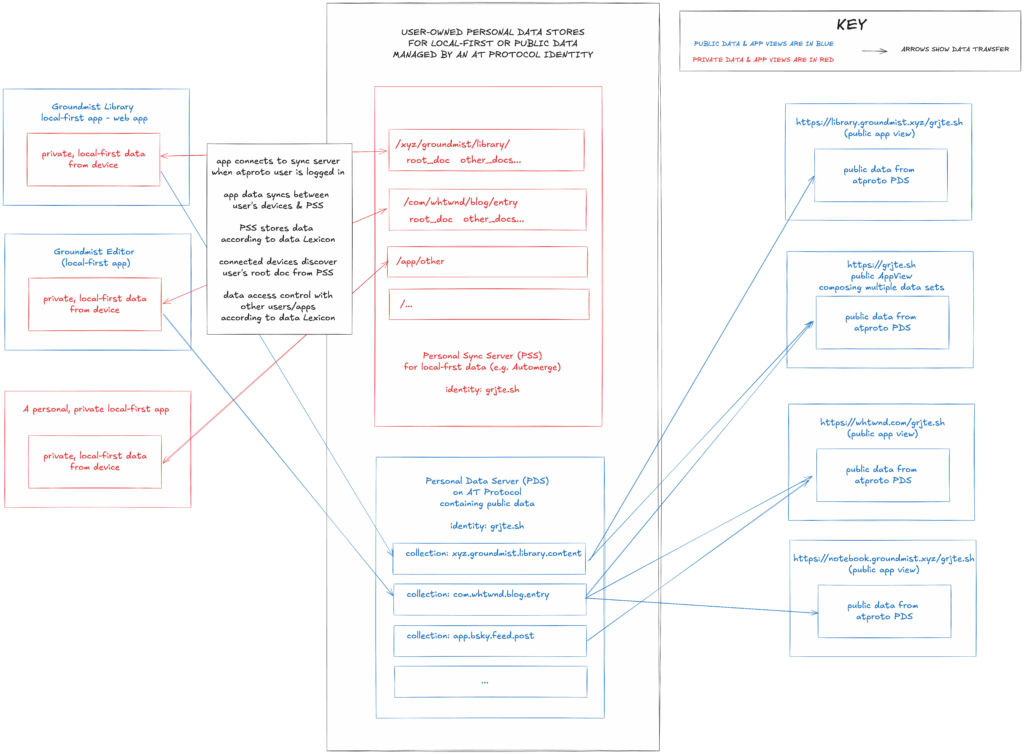

This is the third exploration connecting local-first software with the AT Protocol (atproto). Previously, I explored how atproto can enable new functionality for local-first software by providing distribution and legibility. Now, I’ll focus on interoperability and composability—how we can combine data from multiple local-first applications, privately and seamlessly.

Local-first software and the AT Protocol

The local-first software movement prioritizes user ownership and collaboration. Data lives locally on your devices, allowing fast, offline-first interactions, and smooth collaboration without compromising privacy or security. However, since local-first software is more of a set of guiding ideals and foundational tools rather than a structured protocol, applications naturally vary in how they store and structure data. This leads to fragmentation, reducing opportunities for data reuse or composability across applications.

In contrast, the AT Protocol is an open, structured network designed around publicly accessible data. It emphasizes user-owned, decentralized storage on Personal Data Servers (PDSes), with flexible data interactions enabled by AppViews and semantic definitions provided by its Lexicon schema network. While this structured approach promotes interoperability, the AT Protocol by design prioritizes public data, making it unsuitable as-is for directly managing private or collaborative data.

In my previous explorations, I leveraged the AT Protocol’s structured approach as an additive layer for local-first software, providing distribution and semantic legibility for data published from local-first applications. However, this still left open the question of how we could improve interoperability and composability for private local-first data without sacrificing its local-first nature.

The problem: fragmented and inaccessible local-first data

Despite local-first software’s strong ideals around user control, seamless collaboration, and multi-device access, achieving these ideals can be challenging in practice, primarily due to data fragmentation.

Local-first software applications typically store data separately and independently. Even if multiple applications are built following the local-first principles, each application usually manages its data in application-specific ways, resulting in fragmented user data. This fragmentation occurs both in how data is stored on local filesystems and within web browsers, where security models such as “same-origin” restrictions severely limit data reuse and composability across applications.

For instance, while desktop applications might allow users to manually organize data in a shared folder, schemas are not standardized and storage formats are opaque. In browsers, data stored in IndexedDB or managed by Service Workers is strictly isolated by origin, making direct interoperability impossible without explicit user export actions.

Because local-first software prioritizes flexibility and decentralized design, there is currently no common mechanism or standard for defining how data should be structured or discovered by other applications. This significantly limits the possibility of composing data from multiple sources, reduces the flexibility of interactions with data, and makes reusing local-first data in new contexts more difficult than necessary.

Example: Imagine using multiple local-first note-taking apps. Without interoperability, you must manually export and merge notes. You can’t easily see combined timelines or connections between ideas. Data fragmentation undermines the seamless user experience local-first software promises.

Why composability matters in an AI-driven world

One might ask why structured interoperability is still important when we can use powerful AI agents to understand and aggregate data. While it’s possible to simply store all local-first data on a single device and point an AI model at it, this solution doesn’t scale well across multiple devices and environments. Furthermore, browser-based local-first applications remain completely inaccessible due to browser-origin restrictions, and manually exporting data undermines the frictionless user experience that local-first software promises.

Clearly defined schemas and discoverable data locations enable AI agents to reliably access and manipulate data across multiple devices and applications, providing greater consistency, accuracy, and convenience. Structured interoperability allows AI to effortlessly generate insights, summaries, or recommendations without manual data export and aggregation.

Example: A personal AI assistant could instantly synthesize insights from your notes, calendar, and reading history stored across multiple local-first apps, without manual intervention.

Personal sync servers unify local-first data into user-owned data stores

Personal Sync Server: A user-owned server that syncs your data across multiple local-first apps into a centralized store, making it easy to reuse and compose your data in new contexts.

To enable reuse and composition for local-first data sets, all that’s needed is to shift from using application-specific sync servers to using personal, user-specific sync servers.

The current application-based approach syncs all documents associated with an application to a shared data store that all users connect to. With the personal sync server approach, all documents associated with the same user are synced to a personal data store that the owner connects to. This is a design shift that other teams like Tonk have also started exploring.

The personal sync server is a simple but powerful shift that:

- – Centralizes fragmented data from multiple apps into a user-owned data store

- – Enables data reuse and composability in new contexts

- – Aligns directly with local-first ideals (privacy, user control, multi-device access)

Utilizing data from a personal sync server requires legibility and discoverability. The software must understand its format and meaning and know where to find it. In my previous work, I suggested using ATProto’s Lexicon schema system for data type definitions, to provide structured and available schemas. The structure of the Lexicon system can also be used for discoverability by storing data on the sync server at a path determined by the NSID hierarchy of the lexicon id.

For example, documents using the WhiteWind lexicon with NSID com.whtwnd.blog.entry would be stored at /com/whtwnd/blog/. Storing data along this path also sets the stage for a granular capability-based authorization model for access control when applications seek to read or write to data stores associated with other application lexicons.

Finally, there should be some shared authentication across devices in order to control access to the personal sync server in a simple, user-friendly way. AT Protocol defines an identity system that allows users to control and move their identities, so their identity and data are never locked to a specific provider or service. This portable, user-controlled identity is well-suited for ownership of the personal sync server.

How do personal sync servers compare to existing solutions?

While existing solutions like iCloud Sync or third-party apps like Sync.com have improved significantly (notably iCloud’s Advanced Data Protection), they still fall short for local-first interoperability:

- iCloud Sync: Great UX for Apple ecosystem, but limited outside Apple devices, forcing reliance on proprietary infrastructure and opaque formats. Data portability and composability are constrained.

- Third-party apps (e.g., Sync.com): Good cross-platform support, but typically lack schema standardization, discoverability, and flexible interoperability across diverse applications. Security relies heavily on third-party trust models and client implementations.

In contrast, a personal sync server built around user-owned identities and standardized schemas (Lexicons) aligns directly with local-first principles, ensuring greater flexibility, transparency, and control.

Groundmist Sync: a self-hosted personal sync server

I explored this idea by building Groundmist Sync, a personal sync server prototype linked to your AT Protocol identity. When deployed, your Groundmist apps automatically find it through your public identity. After authenticating via your atproto account, apps seamlessly sync data using structured paths based on Lexicons (e.g., /com/whtwnd/blog/).

Groundmist Sync provides seamless, structured syncing to a personal data store using your AT Protocol identity.

When you deploy Groundmist Sync, you create a personal sync server that is linked to your AT Protocol DID and located at the domain you configure. This domain is published to your atproto PDS so it can be easily found by applications, which connect to your Groundmist Sync when you authenticate with your atproto identity.

For example, when you log into Groundmist Library or Groundmist Notebook, the application will first query your PDS to learn the location of your personal sync server. Next, it sends an HTTP POST connection request using your atproto access token and specifying a Lexicon NSID “group” for the data that will be synced. Groundmist Sync verifies your atproto access token and then issues an access token for connection with the sync server.

With the Groundmist Sync access token in hand, the application opens a websocket connection, and Automerge documents begin syncing to the repo specified by the NSID “group”. For example, the Groundmist Library application, whose documents adhere to the Lexicon with NSID xyz.groundmist.library.content, specifies the lexicon group “xyz.groundmist.library”. it connects and stores documents at /data/xyz/groundmist/library/.

This change doesn’t affect the functionality of the application for users who haven’t set up a personal sync server. It’s purely an additive layer that enables users to unify application data from this and future applications in a way that gives them more flexibility and control. User data remains user-owned and local-first applications remain local-first, but users gain the power of data reusability, composability, enabled by the AT Protocol’s identity system and structured lexicon schema system.

One interesting property of this design is the resilience of the user-owned data store. Although the personal sync server unifies the data in a central location, a new data store could be rebuilt at any time simply by connecting the applications to a different personal sync server. By using the right authorization patterns, data can even be kept encrypted while on the sync server and decrypted locally.

Future work

Groundmist Sync is an early exploration, and several challenges remain:

First, it’s lacking an an authorization layer for access control protections around data reusability and composability across the various data sets on the sync server. Similarly, the current mechanism for syncing to structured locations on the server is restrictive. Future work should address granular access control on the sync server, possibly using something like Keyhive or UCAN.

Second, the personal sync server model disrupts the collaborative capabilities of local-first software, unless an app-specific sync server is also provided for sharing between users (as we do for Groundmist Library and Groundmist Notebook). Although it is still possible to share directly over a variety of transports, sharing with someone far away is more difficult without a sync server that both parties can access. However, if a shared sync server is used, then document authorization needs to be made more robust, since it currently operates under the “swiss number” model of security through obscurity.

Finding effective ways to enable collaboration without losing the benefits of data unification is something to explore. One interesting direction to pursue might be a federated model where personal sync servers sync documents directly between each other once users have authorized access permissions.

We welcome your feedback: @grjte.sh or grjte@baincapital.com.

Thanks to amplice, Kobi Gurkan, and Boris Mann for helpful feedback on this work.

Skip to content

Skip to content